With this blog’s one year anniversary, I want to uphold my tradition of putting lots of effort into things no else cares about, so let’s talk about some older shoujo manga by Shimizu Reiko! The depth and variety of her work represent a golden age of shoujo manga to me: the mid-80’s to mid-90’s. There was a lot of freedom and creativity and classics like Tokyo Babylon, Banana Fish, Boku no Chikyuu wo Mamotte, and more were born. One of my favorite (now all but extinct) movements in shoujo manga was the creation of vast, imaginative worlds within sci-fi stories by mangaka like Hagio Moto, Hiwatari Saki, and Shimizu Reiko. Within these examples, Shimizu Reiko wrote some of my favorite shoujo stories ever about two robots, Jack and Elena.

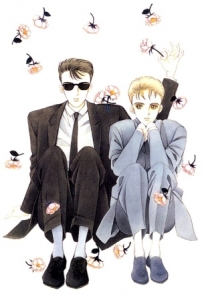

Featured in multiple manga, Jack and Elena are highly functioning androids who couldn’t be more different, yet complement each other perfectly. Jack is nearly indistinguishable from normal human beings, to the point he wasn’t aware of his own nature at first. Jack is what shoujo lacks these days: a handsome, older male lead who is not perfect, not an asshole, and not a bumbling fool. He’s kind and good-natured at heart, but level-headed and capable. He’s a gentleman that cares for others and is one of the most human characters I’ve seen to date. Yes, even though he’s technically a robot. In fact, these robots offer some of the most genuine glimpses of human nature that I’ve encountered in shoujo manga.

Elena is introduced later and is Jack’s polar opposite. She’s undeniably a robot: sexless and built to be strong, beautiful, and perfect. She speaks many languages, is able to communicate with animals, and generally can do anything she tries with great skill. And she knows it. Elena has a dangerous edge: she lacks the level of compassion, empathy, and ethics that Jack has and he often has to curb her actions. Her need for his guidance and his need of–well, being needed–is one of the key elements that make these characters work so well together.

I want to briefly highlight the works these two appear in and some central themes you can expect. I own the original books, so my information doesn’t quite align with the more recent bunko volumes. I ordered them roughly by Jack’s personal timeline, not necessarily date of publication.

Metal to Hanayome

Published in LaLa in 1985, the oneshot “Metal to Hanayome” introduces us to Jack Nigel and the setting, philosophies, and ethics of his universe. And it is a universe–Jack’s adventures span many different worlds and cultures.

Jack

Jack is assigned to kill a well-guarded politician. Needing a way “in,” Jack approaches the man’s beautiful young daughter, Elle. But Jack is confronted with a big obstacle–she has a protective, suspicious robot servant, J. In this time, robots look convincingly human and some practically indistinguishable unless closely inspected. However, robots aren’t given the same respect or rights as humans. Jack is uncomfortable around J and dismisses him as a mere machine, believing J to be an emotionless puppet that mimics emotions.

Jack falls in love with Elle, so when the time comes to kill her father, he hesitates. During a confrontation with J, Jack suffers a grave injury and loses an arm. But there’s no pain, no blood: Jack is a robot himself, implanted with false memories and so indistinguishable from humans that he himself didn’t realize it. Grappling with this shocking revelation, Jack leaves Elle to marry the one she really loves, J. Thankfully, Jack wanders off into a number of follow-up manga!

22XX

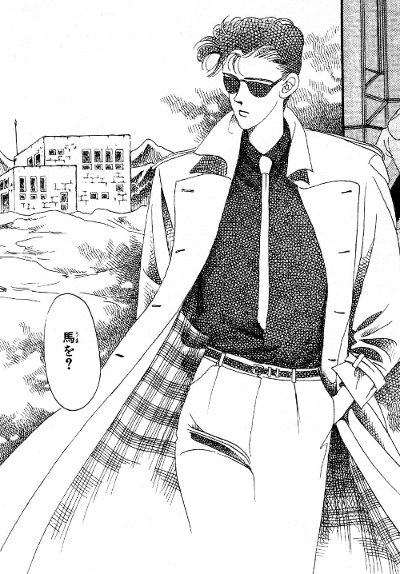

Jack appears in 22XX (1992), a work about environmentalism and social intolerance. Jack is a freelance bounty hunter, essentially wandering the stars with no true purpose. He comes to a planet with a native humanoid race that practices cannibalism. It’s an integral, revered part of their nature and culture. 22XX is interesting because it manages to romanticize the act of cannibalism. At a key moment, Jack hesitated to consume another person’s flesh that was sacrificed and offered to him. Filled with regret by the end of the story, Jack has his programming modified so he’ll never experience hunger, one of his “human-like” traits, ever again. It’s one of those endings that just hit you.

Jack always keeps it classy.

Milky Way

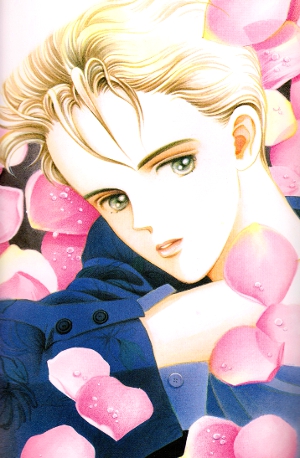

Elena. Shimizu Reiko has a talent for androgynous beauty.

Since Jack is an unaging, undying robot, he sometimes feels alone, despite forming close relationships with humans. This is true until he meets his counterpart, Elena, in Milky Way (1983-86). Jack is a bit jealous–Elena is everything he isn’t and what you’d expect a robot to be. Smart, strong, multi-talented… while he himself is just as flawed as any human, by purposeful design. While perfect by design, Elena has issues as evidenced by her suicide that Jack witnesses by chance when they first meet. Elena has no reason to live and has attempted to fix that–40 times now. Robots are considered valuable resources, so Elena’s always repaired against her wishes after each attempt. However, after seeing Jack, she no longer wants to die. Elena is drawn to Jack because he physically resembles her dead human master Tenryuu whom she was completely devoted to. After some time, Jack realizes he loves Elena, but will Elena ever see past the face of her beloved Tenryuu and look at Jack himself?

Tenshitachi no Shinkaron

Unlike Jack, Elena doesn’t get along with or even attempt to interact or understand humans, particularly women. Elena can’t tolerate human women because in the past, Tenryuu’s fiancee ridiculed Elena, saying robots aren’t capable of love and left a deep scar on Elena’s heart. Tenryuu’s fiancee claimed only humans can experience true love because their mortality and biological drive naturally pair them up for reproduction. (Okay, Elena was onto something thinking she was a bitch~) Robots never age or die, so they are perfect beings capable of living life alone. Does Elena truly dislike human women or is she just jealous because she wants to become one herself?

The theme of Tenshitachi no Shinkaron (1988) centers around the issue of children. It deals with the attachment of robots to human infants and children and Elena’s own feelings about her inability to produce children and how that reflects on her self-worth as a living being. Can living beings really grow and evolve without going through that experience? These are all personal issues Elena must confront and you can’t help but empathize with her conflicting anger and sadness. It’s a beautiful story.

The theme of Tenshitachi no Shinkaron (1988) centers around the issue of children. It deals with the attachment of robots to human infants and children and Elena’s own feelings about her inability to produce children and how that reflects on her self-worth as a living being. Can living beings really grow and evolve without going through that experience? These are all personal issues Elena must confront and you can’t help but empathize with her conflicting anger and sadness. It’s a beautiful story.

There are two additional side stories in the original tankoubon that focus on Elena’s character development. Sen no Yoru is about a time before Elena met Jack when she acted as the guardian of a young girl. In Gekka Bijin, Elena meets the only woman (besides Jack’s ex-lover and their still current friend) that she’s ever truly respected.

Ryuu no Nemuru Hoshi

Ryuu no Nemuru Hoshi (1986-88) returns to the present timeline where Jack and Elena work together as freelance detectives. They travel to a planet where dinosaurs once roamed free. However, human encroachment and fighting have endangered the animals and their habitats. Jack and Elena are caught between a long-standing conflict between two tribes. Elena’s dark, forgotten past is somehow linked to the leaders and threatens her continued existence with Jack. This work features commentary on politics, environmentalism, tradition, intolerance… a common characteristic of her works is that they are loaded with these topics, yet manage to still be relevant a couple decades later.

Being a 5 volume series, there’s more time to further develop the unique relationship between Jack and Elena. You can really see how far these two have progressed, both in their personal growth and in their relationship. Sometimes it seems these two aren’t given quite enough screen time due to the complicated overall plot, but I enjoy every glance we get.

This marks the end of Jack and Elena’s regular appearances in Shimizu Reiko’s works. However, they do have some cameo appearances in her free-talks in Moon Child and there’s a considerable amount of illustrations available in her artbooks. I still have yet to read something quite like it… but I hope to find another someday!

If anything is to be learned from this, the next time someone says something along the lines of “shoujo is all the same,” “it’s boring and shallow,” or “it’s all about high school drama and romance,” you can tell them to stop being ignorant and read Jack and Elena’s adventures.

Wow, this looks really interesting. Classic manga has kinda passed me by, since I started reading manga in late 2008. I think I’ve said before that when it comes to classic manga, art plays a pretty big role for me, simply because sometimes the art is SO sketchy, it’s hard to figure out who is who and what they’re doing.

I’d really like to read this series now, I checked MAL for info as well. Feels like I might discover a new nice side of shoujo manga, because just like you said, when I hear shoujo manga, I immediately think of school romance.

Thank you very much for this post^^

I feel like I have a gap as well. I’d love to read more classics, but it’s hard knowing what to pick. Especially since I have no access to cheap used manga anymore, it means it is risky/can cost a lot It’s hard to find recs for old, non-popular stuff. But I *love* old Hana to Yume. Shimizu’s art is pretty illustrative in showing what’s going on, at least.

It’s hard to find recs for old, non-popular stuff. But I *love* old Hana to Yume. Shimizu’s art is pretty illustrative in showing what’s going on, at least.

I’m glad you found this post useful 🙂 She has a ton of beautiful older shoujo. You can tell her work has been influenced by Moto Hagio (and she has said she enjoyed Shimizu’s work :D). You can find some of her short stories out there already, at least in pieces (Noa no Uchuusen, Mou Hitotsu no Shinwa, Magic, Yume no Tsuzuki are all good). But my favs are definitely Jack and Elena 😀

Random question, but was there a reason you used the “she” pronoun when Elena is sexless? (Although I guess Elena is a feminine name.) Did the Japanese use a feminine reference for Elena? (I know in RG Veda and WISH, a lot of translators used “she” for genderless characters, but some translators use “he” instead.)

No real reason for “she.” “He” looks a bit odd associated with a feminine name like Elena and mostly because it’s different from the “he” for Jack (thus easier to read?). Elena uses a masculine version to refer to her?self, similar to characters like Utena.

I would like to read these manga too (but can’t read Japanese). I love Reiko Shimizu’s works, and I find them very influenced by Moto Hagio too. I also read about Moto Hagio liking Shimizu’s works ^^ as there are less SF works in shôjo manga nowadays (what a pity). Thank you for this interesting article 🙂 . I really find it great to see people blogging about Japanese manga. Is there any chance, as you love SF and old shôjo, to read about Shio Sato’s manga one day?

Thanks! I’ve only read a bit of Shio Sato’s manga. I remember there being a oneshot by her in the Four Shoujo Stories collection that was edited by Matt Thorn. I enjoyed that story, so I’ll definitely consider reading more of her stuff when I’m looking around for more older shoujo manga.

Pingback: Moto Hagio – Univers SF | Errances et phylactères